Bees are in decline.

Or so many environmentalists say , as for example Friends of the Earth with their bee campaign this year. There seems to be no lack of bees in my tiny garden (this photo is of half the front garden).

Almost every time I go out in the garden there is a buzz of bees – and wasps and hoverflies. I could not do a bee count as there were far too many and they were flying all over the place. I admit to not having mastered the identification of the different bees visiting our garden. This along with all the other green scare stories makes be very sceptical about the decline of bees, and particularly the danger of neonicotinoids. (I simply don’t believe anything Friends of the Earth or Greenpeace say, as their knickers are usually smouldering!!) This article makes this clear, but from my observations, which are scarcely scientific, I can’t help wondering whether the replacement of gardens with hard-surfacing and the prevalence of mono-cultures in farming have not made things worse.

However, like most aspects of the environment there is no place for complacency, and appeals for planting more insect/bee-friendly plants should be heeded and acted on.

*******************************************************************

After a decade of debate, the causes of the mid-2000s spike in bee deaths is coming into focus. Culprits are multifactorial, a rebuke of simplistic fingering of pesticides. Time for targeted solutions.

Source: Beepocalypse Myth Handbook: Dissecting claims of pollinator collapse

Myths and truths about bees: There is no dangerous recent decline in the global honey bee population and a class of pesticides known as neonicotinoids are not fostering a global pollinator crisis.

For years, environmental activists and the media have been warning of an impending “bee-pocalypse” in which a drastic fall in the honey bee population, which they claimed was already underway, would threaten bees with extinction and – because bees pollinate much of the food we eat – the word with starvation. The number one culprit in this extinction scenario is a class of pesticides known as neonicotinoids, or neonics, for short.

In fact, the honey bee population did face a crisis in 2006, when honey bee queens began turning up dead in hives and the hive population dove. It is a phenomenon dubbed Colony Collapse Disorder. First GMOs and then later neonics were fingered as likely drivers of the bee deaths.

First identified in the U.S. in 2006, CCD is a still-mysterious phenomenon in which bees simply abandon the hive, often in the fall. But further research showed the CCD is a periodic phenomenon that dates back hundreds of years. Research shows that CCD under other names has repeatedly occurred in Europe, North America and elsewhere.

CCD is likely caused by a variety of factors, most likely climate change and the bees susceptibility to various diseases, with viruses as the main culprit. But CCD has now come and gone as it did many times in the past. According to the University of Maryland’s Dr. Dennis van Engelsdorp (who was part of the team that coined the modern term “CCD”), no case of CCD has been reported from the field for the previous three years.

But the direction of the media narrative, like the travel path of a 250,000 ton ocean liner, was established, and you don’t turn that around very easily. The rebound in bee counts and hives has now reached record territory–news that is just beginning to crack the advocacy firewall meme that beemaggedon is upon us.

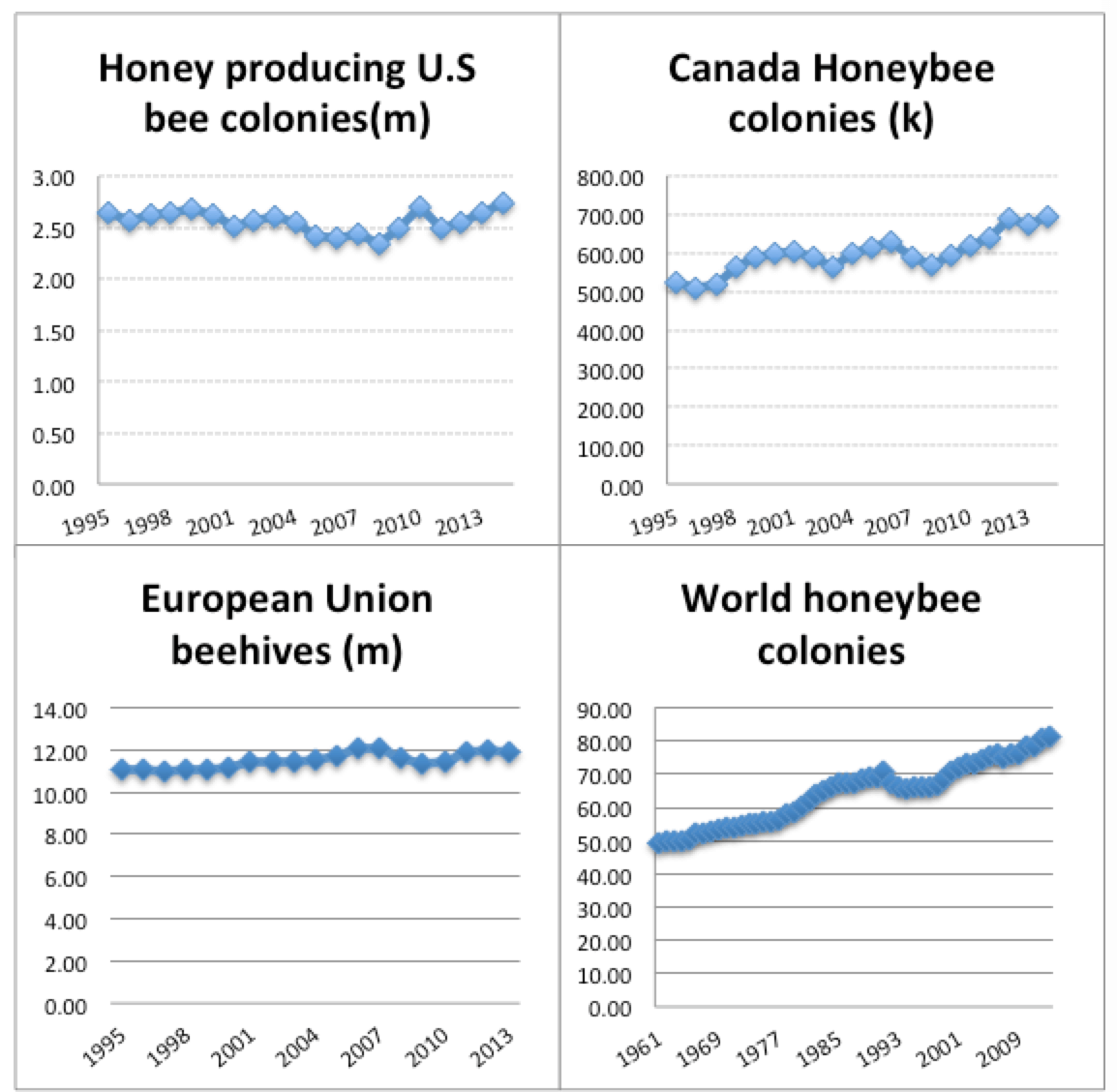

Bee populations aren’t declining; they’re rising. According to statistics kept by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, honeybee populations in the United States, Canada and Europehave been stable or growing for the two decades neonics have been on the market.

Furthermore, the worldwide trajectory for bee colonies has been upward for over half a century. Honeybees are not on the verge of extinction or irreversible decline and the world will not face mass starvation. That’s just scare rhetoric.

What about overwinter and summer losses?

The spikes in bee losses in some parts the world that were seen a decade ago are now mostly a thing of the past, although because of variances in nature, there will always be one region or another with higher than normal losses. It is completely normal for beekeepers to lose a percentage of their hives every year, especially in the wintertime due to weather, disease or the exhaustion of stored food supplies. However, many advocacy groups, and sloppy reporting, have misrepresented over-winter bee losses or added together winter and summer numbers, to make it seem as if the mid-2000s CCD event is ongoing.

Wintertime losses averaged 10 to 15 percent before the U.S. was hit by the varroamite, the deadly parasite that decimates hives and vectors in any number of diseases. Since varroa, loses have risen in some years to 30 to 35 percent. But this does not mean that the honeybee population is in decline.

Over-winter losses are quickly made up each spring, as bees reproduce rapidly.Each queen lays more than 1,000 eggs per day and a worker bee’s lifespan is six weeks in warm weather months. While making up for over-winter losses addscost and work for beekeepers, this is an economic challenge for beekeepers, not an ecological crisis.

Honeybee health problems multi-factorial

Most scientists cite multiple factors involved in bee health problems. By far the number one bee health problem is the varroa destructor mite (see page 15). These parasites suck the bees’ hemolymph’ (blood-equivalent), compromise the bees’ immune system, and vector more than a dozen viruses into bee colonies–making diseases virulent that would normally be easily controllable. Worse, varroa rapidly develop resistance to different mite treatments, making control difficult. Resistance in turn prompts the wide use of bee-toxic mite-control pesticides — the most prevalent chemicals found in beehives — where they accumulate in beeswax (“In virtually any residue analysis of bee bread or beeswax these days in any country with varroa, the most prevalent toxins are the beekeeper-applied varroacides”).

Varroa mites aren’t the only factors impacting the health of bees. Poor nutrition, the dwindling genetic diversity of European honeybees, and some 33 other parasites, viruses, bacteria and other diseases can all make keeping a hive healthy a difficult task. Activists focus on pesticides, but of all the agricultural chemicals detected in hives–including the miticides beekeepers use to control varroainfestations — neonics are generally among the lowest trace amounts detected.

Lab vs. Field: Realistic studies and real-life experience demonstrate pesticides and bees co-exist

Large-scale field studies – four in Canada, one in the UK, four in Europe, most done under Good Lab Practices — have reached the same conclusion: there is no observable adverse effect on bees at the colony level from field-realistic exposure to neonicotinoid-treated crops.

Real world experience coincides with large-scale field study results. In Australia–Earth’s last varroa-free continent–the government’s authoritative report recently confirmed that honeybees there are thriving despite the widespread and increasing use of neonics in agriculture. In western Canada, honey bees are thriving despite annually pollinating Canada’s 19 million acres of 100 percent neonic-treated canola.

Almost all of the research that suggest that neonics harm bees are in artificial environments or laboratory ‘caged-bee’ studies that have been demonstrated to greatly overdose bees. Michael Henry, the French researcher whose study was cited by the EU when it enacted its ban, recently acknowledged,“We have no real clues of what proper, realistic dose you should use in such an experiment,” and, “The dose we have used might overestimate the dose on the field.”

“Bee-Gate” – European activist claims of widespread ecological damage discredited

As the “bee-pocalypse” narrative has increasingly run up against the fact of stable, recovering or in some case rising honey-bee populations, advocacy environmentalists have upped the ante, branding neonics the new DDT and claiming that it is responsible for widespread ecological collapse. The cited foundation for this claim is largely the work of the European IUCN Task Force on Systemic Pesticides. Two recent congressional letters to the EPA–one signed by 60 members of the House, the other by 10 Senators–prominently cited IUCN findings among the reasons for an immediate ban on neonics.

But the IUCN Task Force has been completely discredited in a scandal now known as “Bee-Gate.” In a story carried in the London Times and numerous other publications, a leaked memo quotes Task Force scientists conspiring to fabricate their studies as part of a “campaign” to have neonics banned.

Wild bees appear fine, but should be monitored as hard evidence scanty

There are no reliable population numbers on wild bees–data is just not widely available–which has opened the door to speculation about wild bee health. There have been a few claims of alleged problems, but the evidence is almost non-existent at this time. The limited data that does exist suggests there is no crisis. A 2013 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencesanalyzed U.S. native bee populations over a 140-year period. Of the 187 native species analyzed individually, only three declined steeply, likely due to the introduction of a pathogen. This can hardly be considered a total, or even partial, population decline. Indeed, many experts studying wild bees are not worried. According to USGS’s Sam Droege, one of the foremost authorities on native bees in the U.S., his observations tell him that most wild bees are doing just fine. That said, because of the critical role that pollinators play in nature and agriculture in particular, the government is wise to continue closely monitoring the bee population in the coming years.

Genetic Literacy Project staff